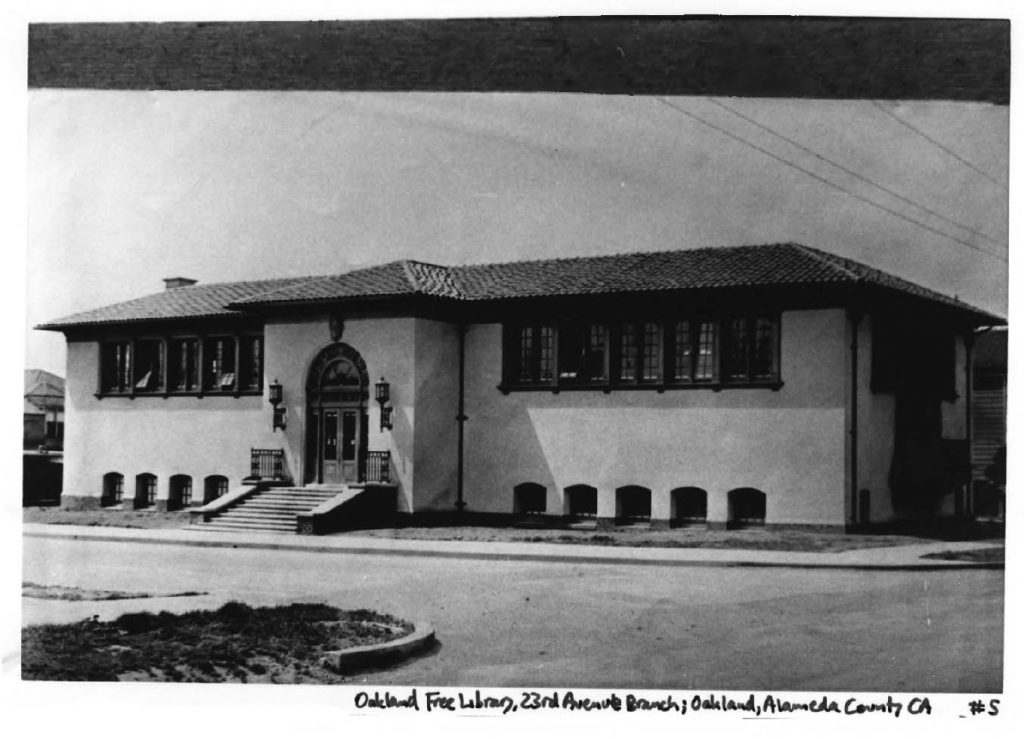

On March 14, the city of Oakland might have celebrated the 100th birthday of one of its landmark libraries. The library at 1449 Miller Ave. officially opened that day in 1918, one of four branch libraries constructed through a grant from industrialist Andrew Carnegie. While they each have a distinctive character, the Miller building, said Leila White, director of Library Services in 1989, was the most beautiful of them.

But on Feb. 23, a large fire gutted the historic building, ending any hope of restoring it. In truth, its destruction lasted for decades. It was left vacant in the 1990s, required extensive seismic repair, and was often home to squatters. It was a protected city landmark since 1980 and on the National Register of Historic Places since 1996, but the city did little to maintain it.

Over the years, many people urged the city to restore the building for public use. Activists took over the building in 2012 intending to operate it as a library again, but Oakland police removed them. They eventually started a long-running community garden project outside. Shortly after the occupation, Valerie Garrie, vice chair of the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board, wrote to then-Mayor Jean Quan and other city officials urging them to restore the library, saying, “The City’s regulations require a duty to keep in good repair and to maintain Landmarks to prevent their deterioration and decay.”

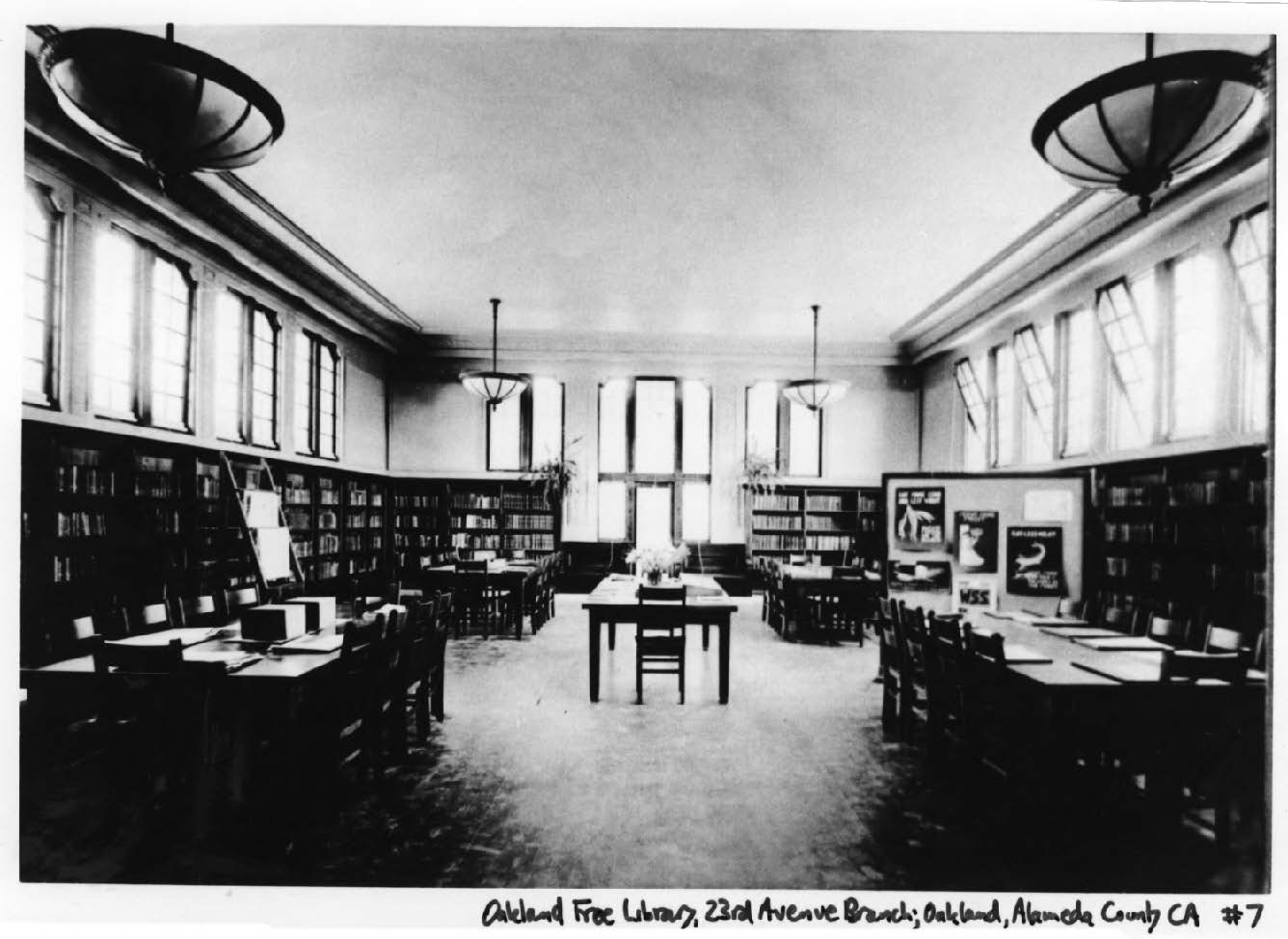

While it hasn’t been a library since the 1970s, there is a rich history at the Miller Avenue building. It grew from a reading room on 23rd Avenue — one of the first branch libraries in California — that opened in 1878 in the easternmost part of Oakland at the time. When the city received the $140,000 Carnegie grant in 1914 to open four new branch libraries, it was the second branch built.

The neighborhood around the library grew steadily over the next decade. The branch’s 1929 annual report described new apartments, houses, restaurants, stores, and factories springing up nearby. Their patrons included many immigrants who worked at factories in Jingletown, so the library kept Portuguese fiction on hand and provided literature in Spanish, Italian, French, German, Norwegian, Swedish, Polish, Greek, Chinese, and Japanese.

For decades, the library was referred to as the 23rd Avenue branch, but by the mid-1960s, employees there were seeking a name change because the building was not on 23rd Avenue. “People tell us they go up and down 23rd Ave. hunting for us,” the branch’s senior librarian wrote in a 1965 report. It was renamed the Ina D. Coolbrith Branch Library in 1966, honoring Oakland’s first city librarian. The building was renovated in 1972 and reopened as the Latin American Library, but that only lasted until 1975, when it closed as a library for good.

In 1979, the building was leased to the Oakland Unified School District. An alternative high school, the Emiliano Zapata Street Academy, operated there through the 1980s. Named for the Mexican revolutionary, the school took in students who were struggling in traditional schools and provided a social-justice-focused curriculum. Students called their teachers by their first names and had a half-day schedule because many were working jobs.

“I was smart and well-read and flunked classes in 10th and 11th grades because I was bored and cut class all the time,” recalled Amanda Smulevitz, who graduated from Emiliano Zapata in 1985. “I learned more in one year at Street Academy than in both years at Oakland High.”

Emiliano Zapata is still in operation on 29th Street but had vacated the Miller building by 1989. The building had already fallen into disrepair, according to an August 1989 letter from then-Director of Library Services Leila White. “Several fires destroyed the very beautiful carved walnut retablos and the outstanding wrought iron grillwork,” she wrote. “Even with massive and reinforced fencing, the basement was again broken into a few weeks ago and several drug users were arrested in the building.”

White had sought to use the building to store historical books and documents, but in 1993, Oakland’s new director of Library Services, Martin Gomez, wrote to the city’s real estate division that the library no longer wanted to use the site.

The slow deterioration of the building continued. In 1995, the city hired Noll & Tam Architects to determine what structural improvements were necessary to restore the building. The longer the city declined to take action, the more expensive the repairs became. In 2004, the city estimated that it would cost nearly $1.2 million to make necessary seismic and other repairs as well as accessibility improvements. Further foundation and landscaping work and other planned improvements would bring the price tag to $2.2 million.

In 2012, activists took over the space, cleaning it up and stocking the shelves with books in an effort to reopen it as a library, dubbed the “Biblioteca Popular Victor Martinez” after the Mexican-American author. Police evicted them a day later, but they continued maintaining a garden outside and erected a small structure to share books.

The activists’ occupation brought the building to the attention of city officials again. Assistant Director of Engineering and Construction Mike Neary wrote in an email in 2012 that, based on the Noll & Tam assessment, it could cost $6 million to restore the building. The city provided tours to some nonprofits interested in purchasing it, but nothing came of it.

Meanwhile, the building became a target for illegal dumping. Residents complained of mattresses, couches, and buckets of oil left outside, as well as continued occupation by squatters, according to logs of complaints to the city’s Public Works Department. At least one complaint came from City Councilmember Noel Gallo, who wrote, “There are now people living inside the building and have trashed the property even more then it was before.”

The building burned twice in April 2017, reportedly because of squatters. The city received a $1.5 million insurance payout for the fire damage, though it had to pay nearly $500,000 to contractors who responded to the fire, according to public works spokesperson Sean Maher. On April 27, 2017, two days after the second fire, city Risk Manager Deborah Grant reached out to organizers of the Biblioteca Popular on Facebook asking them to remove any equipment from the site in preparation for reconstructing the interior, according to screenshots of the conversation provided to the magazine.

However, the city never allocated the funds and decided to sell it as-is, according to Maher. The city received an unsolicited offer to purchase the building shortly before the second fire, Maher said. On the advice of the city attorney’s office, the city issued a notice on Feb. 21, alerting public agencies and affordable housing developers that it intended to sell the property. But two days later, the fire destroyed the building beyond repair. Maher said in early April that the city was working with a contractor to schedule its demolition.

Of Oakland’s four landmark Carnegie libraries now only three remain: at 4805 Foothill Blvd., at 5205 Telegraph Ave., and at 5606 San Pablo Ave. The others have continuously operated as libraries. But the Miller Avenue library, neglected for decades, is lost.