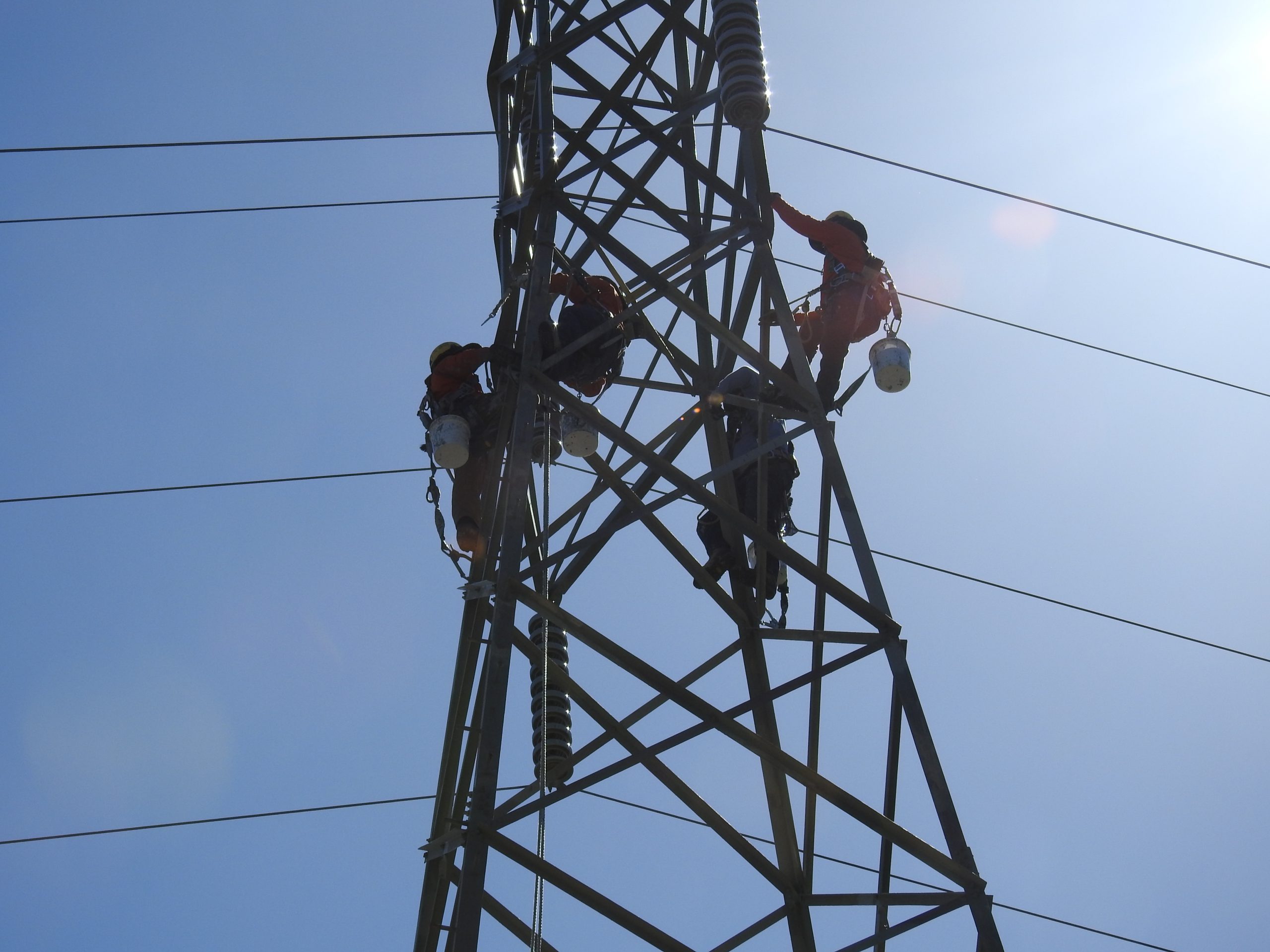

At the end of a narrow, winding street up a steep hill in Orinda, four PG&E workers climbed the lattice of a PG&E transmission tower on a June morning, slathering it with a fresh coat of green paint. They already had carefully stripped the lead-based paint from the tower, and when they’re done, they’ll test the soil below for lead again.

A few days before, they painted another tower across the street. They’ll get to work on another one once they’re done here. In the next few years, PG&E plans to repaint 6,000 of the towers, including more than 1,000 in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

PG&E announced in March that it was ending the use of lead-based paint on its transmission towers. Of the 46,000 towers in its service area—which approximately stretches from Bakersfield to Oregon—6,000 are still coated in lead-based paint, including some dating back to the early 1900s.

Because repainting each tower can take several days, the project is expected to last three to five years. PG&E is prioritizing towers that are closest to people, such as near neighborhoods, parks, and schools. Of the nearly 474 towers still coated in lead-based paint in Alameda County, 85 are in these high-priority areas and will be painted in the next 12 to 18 months, with the work starting this summer.

Three towers in Alameda County are within 500 feet of a school: Lincoln High School in San Leandro, Montera Middle School in Oakland, and William Hopkins Junior High School in Fremont. They will all be repainted this summer while school is out of session, according to PG&E spokesperson Nicole Liebelt.

The fact that PG&E had still been using lead-based paint until recently on its transmission towers is not widely known. The East Bay Times reported on two neighbor complaints of peeling paint from the towers in Contra Costa County in 2015, but aside from that, even environmental groups and PG&E watchdogs were unaware the investor-owned utility was continuing to use lead-based paint.

The health risks of lead-based paint are well documented. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development calls it “highly toxic,” warning that it can cause brain damage when ingested, particularly in young children, leading to learning disabilities, seizures, and even death. The health risks led to the ban of lead-based paint in homes in 1978, but it is still allowed in industrial uses, such as transmission towers.

Lead continues to be an issue in older homes, particularly in Oakland. A Reuters report in December found that Oakland neighborhoods have some of the highest childhood lead levels in the nation, leading the city council to move to beef up its inspection process. Typically, lead exposure comes from chipping house paint in older homes, but lead can also get into the soil so exposure can happen while gardening or when children are playing outside.

While it’s been banned for residential use for decades, the continued use of lead in paint in industrial settings is much more common than most people are aware of, said Perry Gottesfeld, the president of Occupational Knowledge International, a nonprofit organization devoted to mitigating occupational exposures to hazardous materials.

“What shocks people is not just that there’s all these structures in our midst that are coated with lead, but that it’s still legal to recoat these with lead if they wish,” Gottesfeld said.

Lead-based paint might also might be found on water tanks, bridges, and roads. Its use is more common on the East Coast and in the Midwest, according to Gottesfeld, and it has become an issue in New York City recently as lead-based paint chips have been chipping off elevated subway trestles in Queens.

The Golden Gate Bridge’s unique color was originally lead-based paint, but a nearly 30-year project to repaint it with an inorganic zinc silicate primer and vinyl topcoat wrapped up in 1995. While Caltrans hasn’t used lead paint since the early 1970s, some of the structures it owns are still coated with lead paint, raising challenges for renovation and demolition projects. Most recently, Caltrans had to contend with how to keep lead exposures to a minimum when taking down the old eastern span of the Bay Bridge, according to Robert Haus, a Caltrans spokesperson.

BART, too, hasn’t used lead paint in decades. “There isn’t much paint to begin with in our stations as the structures are mostly concrete, but there are a few locations, which have been well maintained, that do have original lead paint in the walls,” Taylor Huckaby, a BART spokesperson, wrote in an email. “However, unless the paint is deteriorating and flaking or in danger of being disturbed due to reconstruction/renovation, it poses little risk.”

Gottesfeld said the costs of working with lead paint are already leading many companies and government agencies to stop using it or voluntarily take on an abatement project, as PG&E is doing.

“It makes no sense to continue to use lead paint because there are substitutes for all of it, and there’s no reason for it anymore.” he said.

He’s written papers about the continued use of lead paint globally, including one published in Frontiers of Public Health in 2015 titled, “Time to Ban Lead in Industrial Paints and Coatings.” In it, he argued for the United States to expand its prohibition on lead-based paint for industrial uses, banning its application on ships, cars, bridges, roadway markings, water towers, and electrical towers like PG&E’s.

“There’s just so many millions of these structures that are in our midst that are coated in lead paint and need to be dealt with,” Gottesfeld said. “I think that PG&E taking a proactive stance is a good thing.”

Containment is key when removing the paint, as chips and dust could fly into the air or fall into the soil. One method of containment is to use a tent to prevent it from flying away along with a tarp on the ground, but PG&E has been using a vacuum to immediately suck it up, and that strategy has been working pretty well, utility officials say. The equipment can’t be used on windy or rainy days, though, limiting when they can work.

Workers are checked daily as they leave the job site for lead exposure and every six months to make sure there’s no long-term exposure, and so far they haven’t had any problems, according to PG&E officials.

PG&E is also testing the soil under towers near homes, schools, and parks, both before the paint removal and after, at a radius of 10 to 15 feet and a depth of six inches. The utility sends each sample for testing to a laboratory and replaces the soil if the lead level is above 80 parts per million—the level set by the state Environmental Protection Agency, which is far more stringent than the federal standard of 400 parts per million.